It barely raises any money. It won’t discourage people from buying corporate jets. So why does the president spend so much time talking about it?

The administration is due to release its budget later today, at which point I’ll dive in emerge sometime later with a trenchant analysis clutched in my teeth as I swim madly for the shore.

Meanwhile, a note on something we know will be in the budget: deficit reduction via elimination of the perfidious “tax breaks for corporate jets”. The president seems to have been obsessed with corporate jets at least since The Audacity of Hope, and continues to argue strongly against them at every opportunity; they were a cornerstone of his stump speeches. And have continued to be even after the election ended. In February, for example, he told a Kansas television station that “they don’t need an extra tax break, especially at a time when we’re trying to reduce the deficit. Something’s gotta give.”

This is a bit weird given that President Obama rides on what is essentially the nicest corporate jet in the world. To be fair, the President is quite right that companies do not need a tax break to buy corporate jets. But since they don’t really get a tax break for buying corporate jets, we probably don’t need to spend this much valuable presidential time worrying about this non-problem.

Am I saying the President is lying? No. But the phrase “tax breaks for corporate jets” implies that we’re giving companies some extra subsidy for buying swank private planes. We’re not. This is a quibble over a technical accounting adjustment that in the end, just doesn’t make that much difference one way or the other.

Basically, the Obama administration is arguing that we should stretch out the depreciation schedule for corporate jets from five years to seven years. For those of you who did not major in accounting, let me put that in English: right now, companies that buy corporate jets can expense one-fifth of the cost of the jet every year for five years. The Obama Administration thinks that they should instead be able to expense one-seventh of the cost of the jet every year for seven years. You still deduct the full cost of the jet; you just do so a little more slowly.

If you’re asking yourself how stretching the expense schedule out from five years to seven years could raise a lot of new tax revenue, you’re not alone. Accountants also find it puzzling. In fact, when this started appearing on the stump, it took the ones I asked some time to figure out what the heck the President was talking about.

One answer to your question is that while “closing” this “loophole” doesn’t actually raise much money, our budget forecasting process makes it look like it does–about $3 billion dollars over 10 years. So okay, in the context of a $3 trillion federal budget, that doesn’t count as raising “much” money. But it is something.

But there’s less there than meets the eye. US budget forecasting is done for ten-year periods. So say that American companies buy 1,000 corporate jets a year, with a total value of $10 billion dollars. With 5-year depreciation, the annual depreciation deduction will be $10 billion, saving companies about $3.5 billion in taxes. Every year some new jets are bought, but the same number of old jets wrap up their depreciation, so there’s a steady $3.5 billion worth of tax deductions every year.

Now say we stretch out the schedule to 7 years. We’ll grandfather all the jets that were bought before, so that they still get to use the old depreciation schedule. But all new jets get depreciated over 7 years rather than 5.

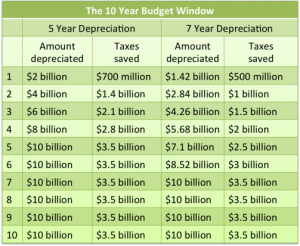

Under the old scheme, the jets bought year one would have been depreciated at 20% (one-fifth) of $10 billion. That’s $2 billion. Under the new rules, we can only depreciate $1.42 billion. In year two, companies are depreciating $2.84 billion (one seventh of the value of the jets bought in years one and two) instead of $4 billion. In year three, total depreciation is $4.26 billion instead of $6 billion, in year four it’s $6.68 billion, and so forth . . .

Here’s what that looks like in a table:

As you can see, by year seven, we’re expensing the same amount. So why does it look as if accelerated depreciation is costing us money? Because during the first five years of the new schedule, the depreciation amounts are slightly lower.

To put it another way, if we forecast 5-year depreciation over a ten-year budget window, we will capture 100% of the depreciation for jets purchased in the first five years. If we stretch the schedule out to 7 years, the forecast window captures 100% of depreciation only for the jets purchased in the first three years. At least some of the depreciation for the rest of the jets stretches beyond the window.

But there’s another answer, which is that depending on your assumptions, it might actually raise some revenue. One reason is that people might decide that it’s not worth buying corporate jets if their annual tax deduction is smaller. But while I’d believe this if we were stretching out the depreciation schedule to 30 years, I find it hard to accept that an extra two years is going to make that much difference.

The other is what economists call the “time value of money”: a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow. That is, if I offer to come over to your house and give you a dollar today, or come over to your house and give you a dollar a year from nex Monday, you’d rather have the dollar today.

This is true even if there’s no inflation, because a dollar today is more useful than a dollar a year from now. After all, you can always save today’s dollar and spend it a year from now. But you can also spend it any time between now and then, which means it offers you some option value that the later dollar doesn’t.

So the question is, how much is accelerated depreciation worth? This is, in some sense, an unanswerable existential question. But accountants have an answer to those sorts of questions: they slap some prosaic, easily quantifiable number on it and plug the number into their equation.

In this case, the three key variables are first, how high is inflation? Second, how much does it cost you to borrow money? And third, how long do you have to wait?

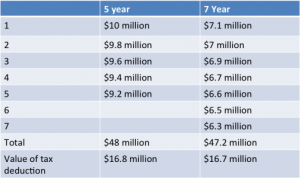

We know the answer to the first and third questions: inflation is far too low to make any significant difference. Here’s what that table above looks like in “real” (inflation adjusted) dollars at 2% annual inflation. As you can see, there’s some difference, but not enough to scuttle the purchase of a $50 million jet–or raise significant money for the Treasury. And since “core inflation” is actually running lower than 2% right now, the actual benefit is even smaller than what I’ve shown here.

That leaves us with borrowing costs. That’s the most interesting question, because there are two ways of looking at it: the borrowing costs of the treasury, and the borrowing costs of the company. If the treasury lets you accelerate the depreciation of your jet, they’ll collect less tax revenue now, but more in year six. In between, if they happen to need that money, they might have to borrow. So in theory, we should probably account for the interests costs of, say, a five-year treasury note.

But if you look at those costs, they’re really low–lower, even, than inflation. The average yield on a 5-year Treasury is just 0.7%. This barely moves the needle.

What about the company’s borrowing costs? Yields on corporate bonds are running more like 3%. That’s a little bit more than inflation–but not that much more. And borrowing actually costs the company something less than that, because the interest is tax-deductible.

Moreover, most companies aren’t borrowing right now. Corporations are sitting on hoards of cash, either because they’re worried about the future, or they can’t find a good use for the money. So a company buying a corporate jet probably won’t need to borrow money if we stretch out the depreciation schedule; they can just dip into the company vaults to cover the higher tax payments.

All of which leads to the same conclusion: the depreciation schedule doesn’t matter. It doesn’t cost the government much money, or significantly change the cost-benefit analysis for corporate jet purchases. The proposed change has only one purpose: to give President Obama something to talk about on the stump.

If Republicans were smart, they’d already have taken this issue off the table by letting President Obama have his new depreciation schedule, and force him to talk about something that might actually make a difference to the country. At the very least, Republicans-and journalists–should be asking the President to show his math.